At first glance, Humphreys looks like an ordinary American suburb. With K-12 schools, chapels, a library, a big box store, dental and veterinary clinics and a spacious plaza where kids can skateboard and eat ice cream, Humphreys could easily be in Dallas or Denver. It’s the security gates, razor-wire topped walls and the M1 Abrams tanks that stand out. U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys is, in fact, in Pyeongtaek, 40 miles south of Seoul, South Korea.

On a guided tour of Humphreys, Army Public Affairs Officer (PAO) Bob McElroy calls it “our little piece of America.” The Army calls it “the largest power projection platform in the Pacific.” Now in the final stage of a massive base expansion, when completed around 2020, Humphreys will have tripled in size to nearly 3,500 acres — roughly the size of central Washington, D.C. — making it the largest overseas American military base in the world, capping off over a dozen years of transformation and consolidation of the U.S. military footprint in South Korea.

Humphreys is a major helicopter base, home to a rotational Attack Reconnaissance squadron. Attack assets like Apache, Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters fly out of Humphreys mostly at night and the 8,000 foot long airfield is large enough to land C-130s or other fighter jets from nearby Osan Air Base.

The installation has a battle simulation center, small arms range, communications center, and motor pools for servicing Bradley Fighting Vehicles and battle tanks, all poised and constantly ready to “Fight Tonight” while, like any other municipality, managing its own public works, infrastructure, police, fire and real estate.

For the residents of Humphreys — eventually there will be more than 45,000 — there are creature comforts like a “super gym” and 18-hole golf course, a community center for arts, crafts and music, swimming pools, athletic fields, a movie theater, a bowling alley as well as a 200-room hotel for military personnel. This month a 300,000 sq. foot modern shopping center with a scores of restaurants and retail stores will open near the pedestrian-friendly town center.

In all, more than 650 new buildings have been built on what was once rice fields and farming villages. But beyond the saunas and Starbucks, the Yongsan Relocation Plan and Land Partnership Plan are consolidating U.S. bases and other installations in Seoul and near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing North and South Korea.

During Korea’s Japanese colonial period (1910-45), Humpheys was a Japanese military base. At the end of World War II, the United States seized control, renaming the base “K-6” (Korean airfield No. 6) and later Camp Humphreys. Today Humphreys is home to U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) Headquarters, the 2nd Combat Aviation Brigade, and more than three dozen other mission units.

Humphreys also hosts rotational infantry, tank, and artillery battalion units who augment forces on the ground and train at the Rodriguez Live Fire Complex using cannons, tanks and mortars near the heavily militarized DMZ.

The relocation to Humphreys includes soldiers from USAG Yongsan, USAG Red Cloud, Camp Casey, Eighth Army headquarters, and elements of the combined forces command and the Second Infantry Division, uniting 173 U.S. military camps from around the country.

The Army says the move to Humphreys means having to defend fewer sites and being further away from potential North Korean artillery strikes while improving “force posture and operational efficiency.”

Behind fences, gates and walls topped with razor wire, USAG Humphreys is a “little piece of America” where U.S. military personnel and their families enjoy the comforts of home while soldiers train for battle ready to “fight tonight.” Photo by Jon Letman

A More “Normal” Tour

For many years, Humphreys was largely a single soldier post, but under a policy called tour normalization, USFK is encouraging families to join their soldiers in-country, hoping more spouses and kids will be a stabilizing force to counter so-called “camptown” problems like fighting, crime, sexual violence ,and prostitution near bases.

To accommodate some of those families, up to a dozen 12-story modern housing towers are being built, furnished and designed for maximum comfort and convenience.

Leading a media tour of the base, PAO McElroy explains how Humphreys expanded onto farm land granted by the Republic of Korea (ROK) government. He says Korean farmers were given cash settlements by the South Korean government and moved into new houses in the mid-2000s.

Media accounts from the time describe the forced relocations as land grabs accompanied by some of the largest and most violent anti-base protests in modern South Korean history. Dr. Andrew Yeo, an associate professor of politics at Catholic University of America, was there. He recalls farmers and families being evicted from the no longer extant villages of Daechu-ri and Dodu-ri.

“The [South Korean] Ministry of National Defense (MND) had acquired the land through a process of eminent domain…There was definitely land that was rice farms. I saw it with my own eyes; I walked there.” After leaving South Korea for several months, Yeo returned to find the former rice farms and villages cordoned off with barbed wire.

By late winter of 2006, Yeo explains, the ROK government was under increasing pressure from the U.S. to push the expansion project forward, a process delayed by clashes between police and protesters. As winter turned to spring, Yeo says, it became easier to accelerate the removal of protesters.

Yeo, who teaches a course on the politics of overseas U.S. bases, says it’s important for American citizens to understand the U.S.’s large overseas military presence and the cost to host countries.

“Even if, at the end of the day, you think bases are there to provide stability and security — we think about national security, but what about human security or, at the very local level, what cost was it to have this large infrastructure in place? It’s all part of the question of who defines peace and security.”

In the village of Songhwa-ri, surrounded by small vegetable fields just outside Humphreys, as large banners decrying helicopter noise flutter in the breeze, Korean activist Joyakgol reflects on the protests and living with a foreign military presence. He says Americans should learn about the impact of U.S. bases in this country slightly larger than Indiana. “In [South] Korea it’s a small country. If you have a huge military installation like Camp Humphreys, the people will have to live here and will be affected by the noise or the pollution or the crime so it’s very painful.”

Protest banners and flags flap in the breeze just beyond the walls of USAG Humphreys in Songhwa-ri village. The yellow flag reads “Change the flight path” in opposition to U.S. Army helicopters that regularly fly over houses at night, forcing villagers to close their windows. Photo by Jon Letman

No Free Ride

Described as the U.S. military’s largest peacetime construction project, up to 93 percent of the $10.7 billion cost of Humphrey’s expansion is being paid by South Korea under the Special Measures Agreement, which comes in addition to more than $800 million in support of the U.S. military presence in South Korea in 2016, a 50-50 split with the United States, according to a USFK Public Affairs Office spokesperson.

Last year General Vincent Brooks, now commander of USFK, made headlines when he stated that it’s cheaper to keep U.S. forces stationed in South Korea than in the United States while then mayor and presidential candidate Lee Jae-myung argued South Korea is paying too much to host U.S. forces.

Despite this, as early as 2011, President Donald Trump has been inaccurately claiming that South Korea doesn’t “pay us” for providing military defense. During the 2016 campaign he continued to falsely suggest U.S. allies weren’t paying “their fair share.” Last April the U.S. president sparked outrage when he called on South Korea to pay $1 billion for the deployment of the THAAD anti-missile system which maker Lockheed Martin openly states is being deployed “to defend U.S. troops, allied forces, population centers, and critical infrastructure.”

Seoul’s willingness to pay so much for the U.S. military presence, McElory says, is “a sign of the strength of our alliance with the ROK.” He stresses the United States and South Korea share “an important alliance…an important mission,” adding, “we’re equal partners in it and we have each other’s interests at heart.”

Responding by email, Lee Mihyeon, coordinator of the Peace and Disarmament Center of the Seoul-based NGO People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, says her organization does not support Korean tax dollars paying for U.S. military forces: “Of course there are people who accept this expenditure with resignation, but most South Korean citizens are not okay with [it].”

Regarding the question of burden sharing, Dr. Daniel Pinkston, a lecturer on international relations at Troy University in Seoul, says, “The ROK is a democracy, so they can stop it if they want. But they are getting a good deal.”

Writing in an email, he suggests that in light of regional security threats, South Korea spending about 2.6 percent of its GDP on defense is reasonable. He calls South Korean expenditures to keep forward deployed U.S. Forces and credible extended deterrence “a really great bargain,” asking, “What would the alternative be?”

Newly built soldier housing, schools and other facilities as seen from the balcony of a 12-story residential tower. In 2006, the South Korean government forcibly relocated Korean farming villages in order to expand what will be America’s largest overseas military base. Photo by Jon Letman.

Deep Divisions Remain

In addition to the cost of paying for Humphreys’ expansion, Kang Song-won, director of the Pyeongtaek Peace Center, says that more than a decade after villagers were displaced, community divisions remain.

New infrastructure like wider roads near the base and real estate development for military off-base housing, Kang says, benefit U.S. forces, and specific business owners, not the greater community.

The size of the base, he adds, isn’t as important as it once was with the United States exercising a policy of strategic flexibility, meaning U.S. forces can be dispatched from South Korea to other countries as needed. For Kang and like-minded Koreans, being sandwiched between Osan Air Base and Humphreys means living with noise, crime, and a divided community.

When protests against Humphreys’ expansion raged over a decade ago, Kang was joined by Catholic priest and prominent peace activist Father Mun Jeong-hyeon. Father Mun, now 80 years old, still actively protests against U.S. and Korean militarism. “The U.S. military occupies so [much] land here and there,” Mun says. “We insist that U.S. troops should be out of Korea. We cannot allow the U.S. military to occupy Korean land anymore.”

Father Mun asks a simple question: “Why Korea was divided? Why USA is stationed in this country for a long time?”

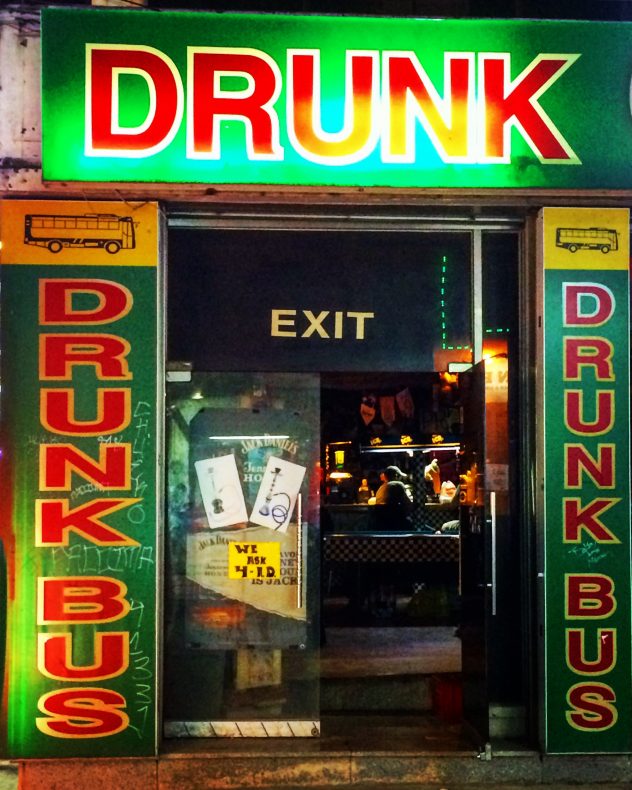

Clubs and bars like the Drunk Bus cater to U.S. military personnel in the village of Anjeong-ri outside of USAG Humphreys. Camptown districts near overseas U.S. bases have a history of crime, prostitution and human trafficking. Photo by Jon Letman.

Ready or Not

Lanae Rivers-Woods, a U.S. citizen who has lived in Pyeongtaek teaching in a Korean public school for seven years, has watched how her own country’s military is changing her adopted home. She says the impact and the response defy simple explanations.

She describes indifference by many in her community for whom Pyeongtaek’s bases — USAG Humphreys and Osan Air Base — are all but nonexistent. She calls the situation “kind of surreal.”

Areas around the U.S. bases have little to offer Koreans, Rivers-Woods says, recalling her own experiences outside Osan Air Base.

“Generally, we all avoided those areas because they were violent and stressful,” she says. “The verbal sexual harassment the second you walked onto the main street [by the bases] was really stressful,” she says, calling it “really inappropriate” and “very uncomfortable.”

Today, however, that hostile atmosphere has changed dramatically according to Rivers-Woods, who calls the situation now “way more normal.”

But as Humphreys draws a huge influx of U.S. military personnel and their families, she worries about what she sees as a lack preparation by the military and the inability to integrate soldiers into Pyeongtaek’s civil community. In response, she has launched her own volunteer organization and created a smart phone app and blog to help military personnel adapt and better understand Korean culture.

“I don’t have anybody’s agenda,” she says, “I am just there to solve problems.”

Pyeongtaek faces many challenges beyond its role as a major military hub. Rivers-Woods points to massive industrial and commercial development, worsening traffic and poor air quality, and rapidly rising housing costs, which she says dwarf local concerns over the expanding military base. “If you saw the other development, you’d be like ‘why would I care about that base?’ I am pretty sure the entire base would fit in the one Samsung factory… We’ve got a lot of issues going on,” says Rivers-Woods.

New Samsung, LG and other large projects are expected to double Pyeongtaek’s population from the current 440,000 in several years’ time.

Kang Song-won of the Pyeongtaek Peace Center points toward USAG Humphreys in the distance as he explains how farmers were displaced by the expansion of the U.S. Army base. Photo by Jon Letman

Abandoned Land

Bridget Martin, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of California Berkeley, is currently living in South Korea studying how base consolidation and U.S. military spatial reorganization impact communities and local development projects.

She spends a lot of time meeting with South Korean government officials, examining how they want to use the land after it is returned by the United States. Projects include parks, restoration of natural areas and commercial ventures. After the United States returns land to the ROK government, it is primarily and controlled by government agencies like the Ministry of Financial Planning and the Ministry of National Defense (MND).

Local municipal governments may want that land but the MND charges market price for the former military sites and, as Martin explains, “No one can afford to do anything with [the land] and it’s already a very economically depressed area.” The result, she says, is a lot of unused, abandoned land.

Meanwhile, the Pyeongtaek municipal government has tried to present the Humphreys’ expansion and troop increase as an opportunity to spur growth, attract new investment and infrastructure development, and transform Pyeongtaek into an international city.

“There is a diversity of opinions in the Pyeongtaek city government for sure,” Martin says, “but the vision for the city kind of congealed around this utopian sort of military cosmopolitan space that I cannot imagine will ever pan out the way it is portrayed in the propaganda and planning material.”

Part of the U.S. military’s largest overseas base includes this newly-built pedestrian-friendly downtown plaza. The 3,454 acre installation will eventually be home to around 45,000 military personnel, their families, civilian contractors and Korean nationals. Photo by Jon Letman

Little Piece of America

Back inside USAG Humphreys, Bob McElroy drives along a main thoroughfare called Freedom Road where, even at a time of heightened rhetoric when the leaders of North Korea and the United States casually threaten each other with nuclear annihilation, life plugs along as usual. Soldiers maintain their vehicles, attack helicopters conduct night training exercises, and military families live a comfortable American lifestyle inside their fortified home.

McElroy says the upgraded base is a way to show appreciation for the men and women of the U.S. armed forces who support the U.S.-ROK alliance, always ready to “fight tonight.” Whether there’s war or peace, the United States shows no sign it plans to leave Korea any time soon.

Surveying the installation from the balcony of a 12-story family housing tower, McElroy says, “It’s interesting to see how much it’s grown and how much it’s changed. It’s a great thing. It’s staggering when I think of the size of this thing and the fact that we built a city out of just farm fields, out of — not from nothing, there were villages out here — but we built it up from the ground up.”

Reviewing the expanded perimeters of U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys on a map, this reporter points to Korean names and asks, “Are those villages?”

“They used to be,” McElroy answers, explaining a new vehicle maintenance facility is being built where the village of Daechu-ri once stood. Gesturing inside a thick black line on the large map, he says, “All of this is ours now.”

Jon Letman is a Hawaii-based independent journalist covering politics, people, and the environment in the Asia-Pacific region. He has written for Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy in Focus, Inter Press Service and others.